Where have I heard this before?

Pro bono: In volunteer work that others can’t afford to pay you for

Carpe diem: In Instagram posts about the spontaneous holiday you can’t afford

Et al.: In papers you can’t afford to turn in without hitting the 3000 word count

Quid pro quo: In negotiations where you can’t afford letting things go

For a “dead” language, Latin seems to be everywhere, even in songs. Today’s offshoot attempts to explore this notion of dead languages and see where Latin fits in.

Knockin' on Heaven's Door

Allow me to borrow from the Princess Bride, the book within a movie based on a book:

Miracle Max: It just so happens that your friend here is only MOSTLY dead. There's a big difference between mostly dead and all dead. Mostly dead is slightly alive. With all dead, well, with all dead there's usually only one thing you can do.

Inigo Montoya: What's that?

Miracle Max: Go through his clothes and look for loose change.

Languages, unlike us carbon-bases lifeforms, do not leave obvious signs of decay and death; no dropping head, no still pulse, no rotting corpse. There are varying degrees of aliveness, and blurred lines between the written and the oral to further complicate matters.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines a dead language as one “that is no longer spoken by anyone as their main language,” i.e. it might still be in use in other forms or as a second language. This is distinct from an extinct language, which is “no longer known, including by second-language speakers.” Many of the 573 known extinct languages are oral languages of tribes and other isolated groups, thus, leaving behind no speakers or ways to revive them. The causes can vary from linguicide (language death by natural or political causes) to glottophagy (absorption of minor dialects or languages by major ones).

A side-note on the arbitrary distinction between language and dialect by Yiddish scholar Max Weinrich:

A language is a dialect with an army and navy.

Vous parlez anglais?

Some place the blame for the recent acceleration of language extinction and death on English, the lingua franca (bridge language i.e. the common language spoken by people with different native languages) of our times.

As the Independent inquires:

How did a dialect, spoken by a backward, semi-literate tribe in the south-eastern corner of a small island in the North Sea spread, like some malign pandemic virus, across the globe?

The emergence and fading away of languages is a complex subject, deeply interconnected with politics, geography, theology, history, socio-economics, and many other disciplines. Want evidence? Look at the death (and birth) of Latin, whose fate is inextricably linked to the Roman Empire.

Founded in 753 BC, Rome was situated in the region known as Latium, and is considered the birthplace of Latin (one of the Italic languages). As the Roman Republic expanded to an empire, its dominant language spread with it. And, unsurprisingly, its decline is tied to the time the Roman Empire fell, transitioning from one empire with one emperor to a collection of states, ruled mostly by invading Germanic kings.

But it did not disappear immediately. In reality, think of it as passing on the torch. Latin had been evolving for decades before the Huns arrived. Old Latin turned to Classical Latin (the form used in most official communication and literature from the era, and hence, still surviving in scholars’ libraries and universities’ Classics departments), which co-existed with Vulgar Latin, the non-academic tongue of the commoners or the middle class (this is a simplification not without its critics so do not quote this verbatim in the public square unless you want to be stabbed by linguists). When the incoming clans collided with the remnants of the Roman Empire, it is Vulgar Latin which evolved and gave rise to the Romance languages (including Italian and French). Yes, French used to be Latin.

In the Middle Ages, while hardly anyone spoke Latin, a form of it (Medieval Latin) was being used by the Church and Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire as the official language (later replaced by German). A renewed interest in Classical Latin was observed (still largely in written form) during the Italian Renaissance in the 14th century, leading to Medieval or Middle Latin’s dethroning by Early Modern Latin.

Veni, vidi, vici

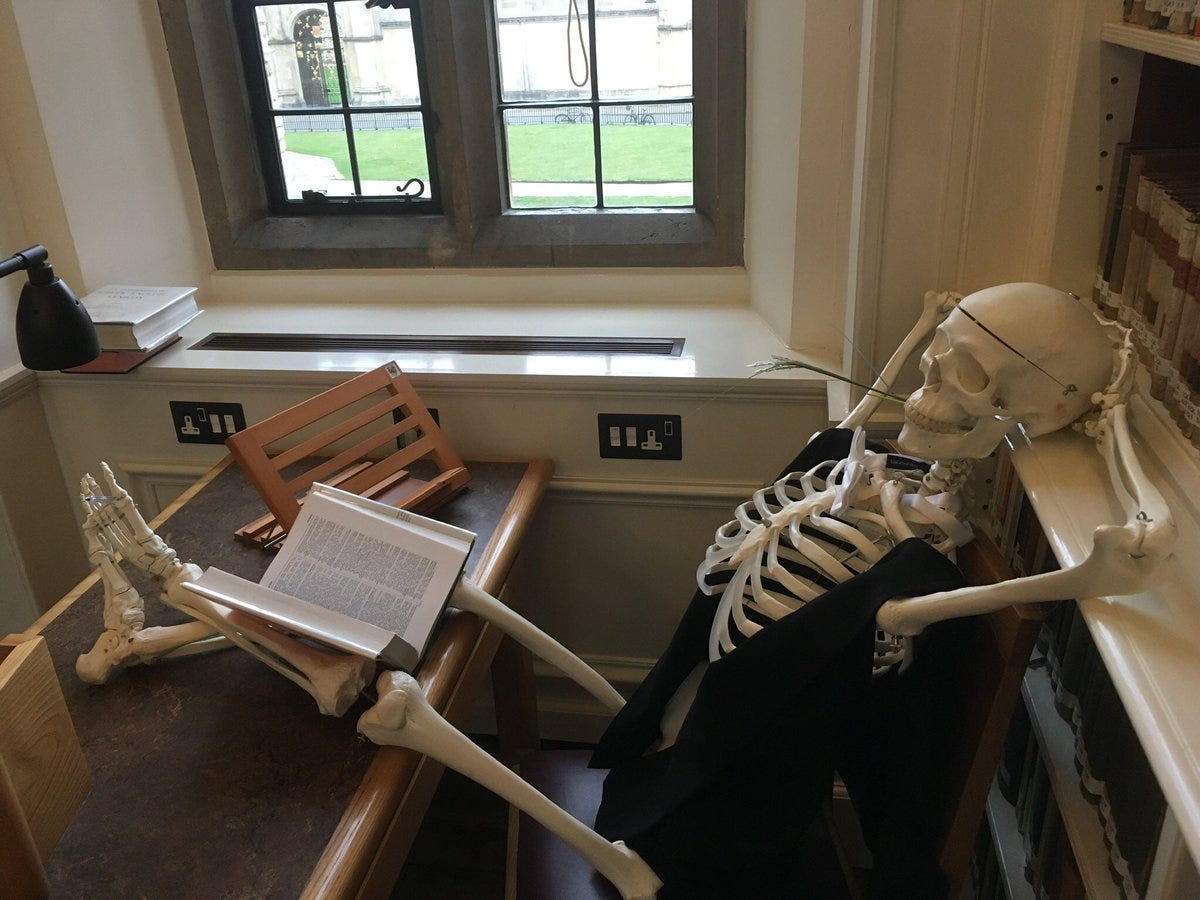

Latin has morphed and shown resilience over centuries, having wormed its way into the lexicon of various languages, official documents, and even Harry Potter spells. If Latin must be termed dead, then call it the walking dead. In a fun twist of fate, the language is often associated with magic spells, in fictional as well as real traditions: a curious case of the dead raising the dead.

And what about Latin’s offspring? There are interesting lexical (related to vocabulary) and grammatical similarities between the Romance languages. Exhibit A:

Interesting differences emerged over time due to social factors. For instance, the R in Portuguese was (historically) pronounced exactly the same as in Spanish or Italian, with a trill of the tongue. But in the 19th century, the guttural R became popular as it was now chic and socially desirable to “French it up” — French being the language of culture and diplomacy in the 18th and 19th centuries, a title it borrowed from Latin (which borrowed it from Greek), and lost to English in the 20th century.

Though languages have different lifespans than us, they do share other features like lineages, family trees, reputations; jumping on and off the carousel of relevance, or in extreme cases, jumping off to meet their demise. And while many linguists agree that 50% to 90% of the 6,000 or so languages in use today could be extinct by 2050, Latin won’t be one of them. Don’t go looking for loose change in its pockets just yet.