In earlier offshoots, we’ve spoken about words invented by authors but some authors are more equal than others. Some truly commit to the playful art of invention- they don’t stop at words, instead they dream up entire languages. Why? Because sometimes, foreign tongues just don’t suffice in getting to the heart of what we want to say.

Ask Tolkien. Not wanting his elves to wander around greeting each other with ciao, he made up a world where it would be normal to say: elen si-‘la lu-‘menn omentielmo (“a star shines on the hour of our meeting”). Other common phrases that pack more punch in invented languages include Dothraki’s Finne zhavvorsa anni? (“Where are my dragons?” for when your dragons go missing in the House of Undying) or Klingon’s Hab SoSlI' Quch! ("Your mother has a smooth forehead!" for when you want to insult the people who hid your dragons in the House of Undying. Those monsters!)

Called artificial or constructed languages (conlangs), these range from fan favourites like Star Trek’s Klingon to the lesser known Illitan featured in the book, The City and The City. Don’t be fooled by their concentration in fantasy and sci-fi works: it’s a nerdy niche no more. There are even apps to help you master these languages.

One of the foremost torchbearers of the conlang community is David J. Peterson with a linguistics Ph.D. from UC San Diego. He is the creator of both Valyrian and Dothraki for HBO’s Game Of Thrones, amongst a few other fictional languages. He can be partially blamed for, sorry, credited with raising the bar for fake languages such that the audience now expects authenticity and verisimilitude- that is, they want conlangs to adhere to some syntax and grammatical rules, and not just be a collection of sounds. In short, Chewbacca’s Shyriiwook grunts won’t cut it anymore.

Once upon a time in Middle Earth

Roots of contemporary fascination with invented languages can be traced back to J. R. R. Tolkien. Years before he carefully crafted Quenya and Sindarin for the Lord of the Rings books, he made up a language based on animal words with Mary Incledon, his cousin. In A Secret Vice, he called this pastime embarrassing and lonely, stating that:

Most of the addicts [people addicted to inventing languages] reach their maximum of linguistic playfulness, and their interest is swamped by greater ones, they take to poetry or prose or painting, or else it is overwhelmed by mere pastimes (cricket, meccano, or suchlike footle) or crushed by cares and tasks.

Now, the tide seems to be turning. Conlangs have found cult followings and vocal communities, some spilling beyond the confines of the internet into the physical world: look at AvatarMeet, the annual gathering of fans and speakers of Na’vi (the fast-flowing, melodious language invented by Paul Frommer). High Valyrian has found a home on Duolingo. Star Trek fans have staged Hamlet after translating it to Klingon. All of these popular artificial languages are members of the conlang sub-category called artlang: languages created with specific aesthetic goals or as integral parts of a piece of art (like a film or novel).

Artificial languages are not always created in the service of an aesthetic purpose, some are designed to serve the utopia most pageant winners dream of: world peace. Consider Esperanto (the brainchild of Polish ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887), claimed to be the most widely-spoken conlang (of a sub-type called international auxiliary language), which was intended to be a language of friendship, facilitating communication amongst people from different countries.

With great power comes great responsibility. As Peterson humorously writes in his book, The Art of Language Invention:

…English, whose orthography was devised by a team of misanthropic, megalomaniacal cryptographers who distrusted and despised one another, and so sought to hide the meanings they were tasked with encoding by employing crude, arcane spellings that no one can explain. (“Ha, ha! I shall spell ‘could’ with an ell! They will be powerless to stop me!”)

Con-a-lang: a DIY guide

Now that you’ve been warned about the responsibilities, here’s a look at some simple steps used to create new languages (I know you’re not exactly dying to compete with Klingon to create some veiled forehead insults of your own, but play along):

Sounds: It all starts with phonetics (the study of speech sounds). Get your vowels and consonants in order. Based on the nature and cultural elements surrounding this new language, determine the sounds that are permitted or not - will there be a trill like Spanish ‘rr’ (rolled r’s) or a guttural French ‘r’? Of course, there can be room for different accents too.

Words: Create the lexicon (vocabulary) for this language and introduce morphology (formation of and relationship between different words) and pronunciation guides. For example, Tolkein introduced nuances in the form of prefixes and suffixes to make his languages more intuitive: consider Moria (“Black Chasm”) and Mordor (“Land of Darkness”), both derived from the root moro- (“darkness”).

Grammar: Time to get technical and create some rules for the grammar Nazis to enforce. Introduce syntax (word-order), or not. For instance, similar to Russian, Na’vi is endowed with a relatively free word order. Tenses, pronouns, gendered words, etc. are all fair game.

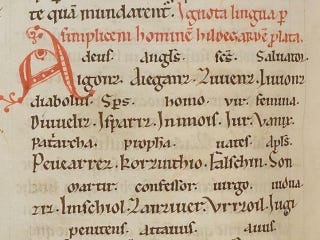

Writing systems: If you have the inclination and are inspired by the One Ring (the one to rule them all? yes, that one), you can move beyond speech and create a writing system for the new language. Scripts and alphabets can be experimented with. It’s not necessary to be grounded in reality here either. Why restrict yourself to Kanji, Hieroglyphs or Devanagari? Create odd symbols to give the language an other-worldly feel.

Oddities and quirks: At this stage, you can add quirks. Make up ridiculous idioms and slang. Add multiple words for the same concept or thing (one which is highly valued by the fictional society - say, chicken) and feel free to skip creating words for other less important ones altogether (say, avocado).

Once the language-building exercise is complete (takes a few years, according to seasoned creators), you can start recruiting people to speak it. How? Easiest would be to sign a deal with HBO only to have 8 years of build-up for a painfully ridiculous ending. Trust me, you too can ruin lives. Believe in yourself. Alternatively, you can try handing out free matcha tea samples to your friends in exchange for a brief conversation in your new secret language. But then again, if we had social lives, we wouldn’t be sitting here discussing language invention.

Greetings, Earthlings

Returning to David Peterson, he theorizes that making conlang a larger community (and not just a punchline for Sheldon Cooper to earn his laugh-track) could even help humanity broaden its understanding of languages in diverse forms. He believes this could be especially beneficial if we receive some unexpected visitors who travel in groups and don’t believe in haircuts (no, not the Manson Family):

Someday in the future we may encounter aliens, and they may have a communication system that doesn’t even qualify as a language to us, that we wouldn’t think of as language.

This concern over how to communicate with species that may or may not exist is not new or unreasonable. After all, we can’t all be lucky enough to find a babel fish (the universal translator from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy). So, allow the imaginative linguists their indulgences because the results can be mesmerizing. Exhibit A: the movie Arrival, whose creators envisioned what alien alphabet might look like.

Besides fictional worlds, nerdy Internet message boards, and inter-galactic pen pals, conlangs can have more earthly, ordinary uses like complaining about those people who cut in line at the airport or make phone calls in movie theaters. Go ahead, speak in secret tongues, find your dragons, and be the Dark Knight with a linguistics degree we all need.